A couple weeks ago, during an Insect Biology Lab fieldtrip to the Spring Creek Greenway, I picked up a leafcutter ant with the specific purpose of having it bite me. Some may use this as evidence that I am crazy and others may cite it as an example of the power of peer pressure, but really it was interesting to get to see the ant up close and personal. It didn’t really hurt that much anyway and, in a weird way, it was kind of cute to watch the ant trying so hard to pinch my skin with its little mandibles. Ok, maybe I am crazy, but that’s not what this blog post is about. Actually, what I found the most interesting about this experience was picking which ant to let bite me. When we look at an ant mound, normally we just see essentially hundreds of copies of the same ant, as though they all popped out of the same mold from an ant making machine hidden underground. However, if you take a closer look, it is really quite a bit more complicated than that. As I scanned the ground, trying to decide which ant to pick up, I heard Dr. Solomon say something about how I should pick up a soldier one since they’re bigger and interesting to look at. That’s when I noticed that within this same species (Atta texana), within this same colony even, there were ants that looked widely different from each other. I had a vague idea about the division of labor in an ant colony before, but I hadn’t really realized the degree of specialization until after more research.

Soldier on my finger. Sorry for the fuzziness. Taking a picture of an ant on your finger is harder than it looks.

According to the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology , Atta texana highly specialize tasks using a caste system. Individuals are either reproductive or workers, and these workers are distinguished by twelve distinct worker morphs. These morphs can be grouped by size which reflects their function. The largest of the morphs are the soldiers, the caste that I personally picked up. The medium sized morphs are primarily foragers, but also function as excavators. Finally, the smallest morphs generally remain in the nest, functioning to break down leaves, care for the colony’s fungus gardens (the true source of food for the colony), and care for the queen and larvae.

Of course, learning about the complexity of the ant caste system made me wonder, “How is the caste of an individual determined?” In my research I found this paper in The American Naturalist about the developmental pathways that lead to caste determination in ants. In the paper, the author defines caste as “a set of workers that develops under the same developmental program”” rather than looking at it from a purely morphological perspective. The three variables that she lists as regulating these castes are critical size ( the size of a larvae once it begins the first step towards metamorphosis), growth parameters (growth rate vs dampening rate), and reprogramming (changes in critical size and growth parameters). The paper goes into quite a bit of detail about all of the factors that affect critical size. The one main means of determining critical size is by the amount of food the larvae receives. This can be driven both by environmental factors (such as the availability of food) or by the regulation of food flow by the “nurse” worker ants. In fact, nursing workers carry quite a bit of the responsibility of caste determination for the larvae as they manipulate the pheromone concentrations and temperature that also contribute to reprogramming. Something that this paper doesn’t address, but would be an interesting thing to find in further research would be the factors that affect the various behaviors of the nursing ants that cause them to drive the caste determination.

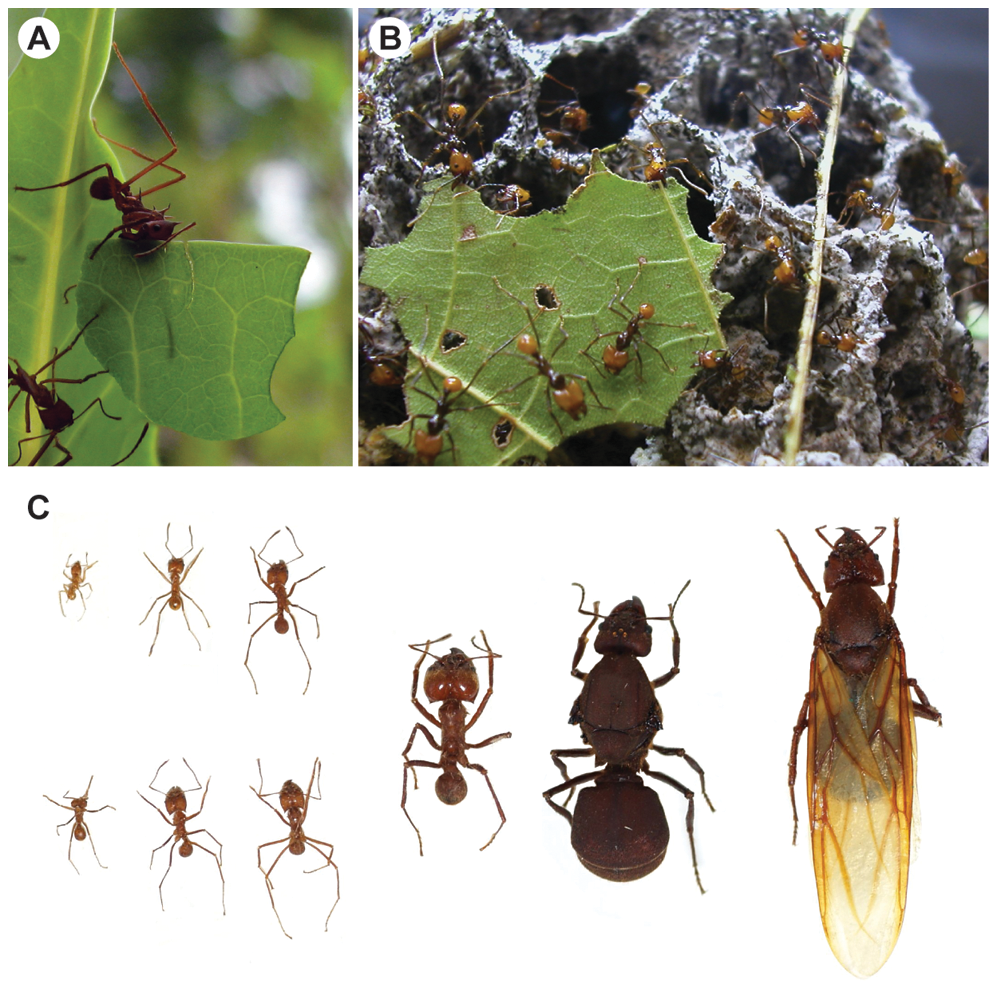

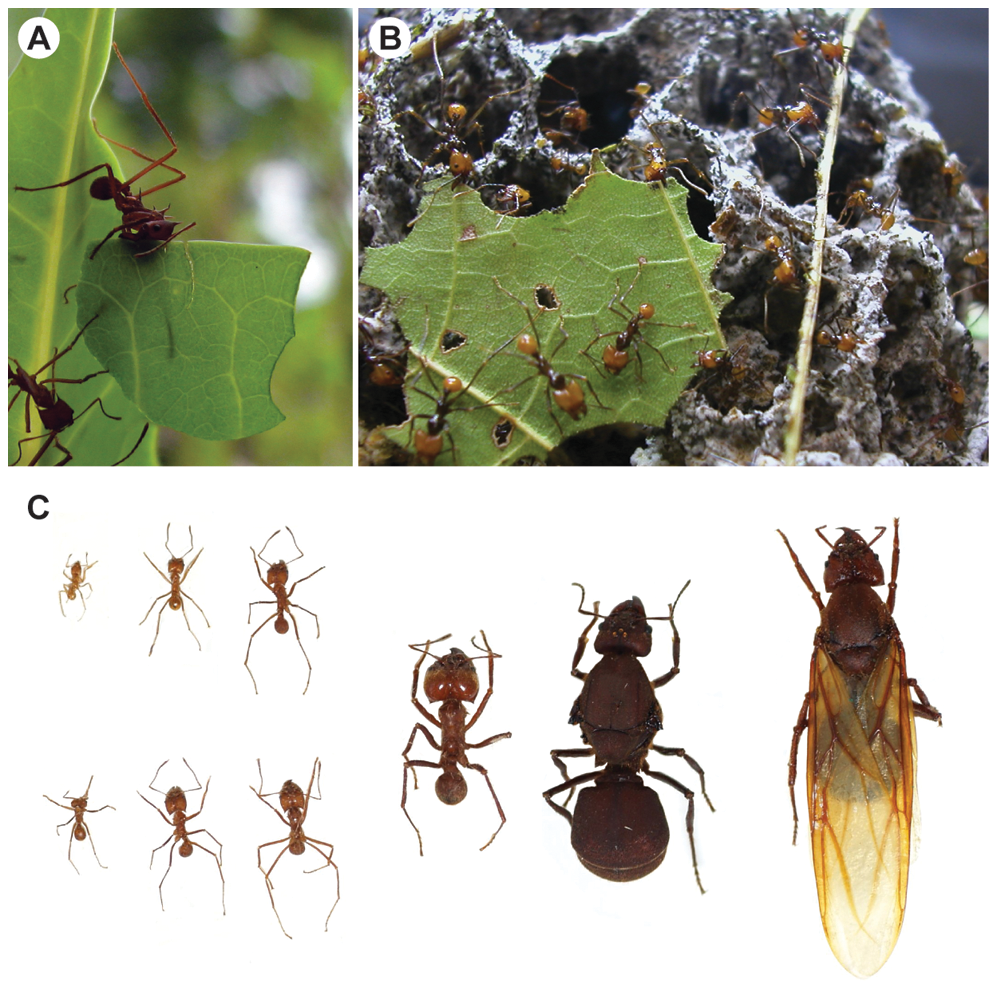

Some examples of leafcutter ants and the polymorphism in their castes. Source:http://www.plosgenetics.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pgen.1002007

While the division of labor through the caste system has its clear advantages in developing specialized workers that improve efficiency, the paper mentioned above also discusses the possible issues with specializing too much and too early in the developmental process. Obviously, a limit has been placed on the number of specialized functions. For the hundreds of thousands of ants in a colony, there are twelve castes. If more specialization equals more efficiency, why not give every individual its own specialized role? Well, as discussed in the paper, with the morphological specialization to one class comes a decrease in “individual flexibility.”

Source: http://trentflix.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/2839-Antz_1.jpg

Remember that 1998 Dreamworks movie, Antz? Of course you remember. It’s the one about the neurotic worker ant (not surprisingly voiced by Woody Allen) who rebels against the injustice of the social structure in his colony and ultimately marries the princess ant. Well, it wasn’t until doing more research into this caste system that I realized that despite its many many inaccuracies, it actually represented a true component of ant colonies and reflected (although with different reasons) the detriments of hyperspecialization. Throughout the movie, the main character is battling against a caste system that restricts his individual freedom. While his objections were more from a human perspective, the concern is still valid to a certain extent.

Form follows function, so if the form stays more general, it has the ability to adapt to new needs within the colony. If for some reason there’s a loss in the number of foragers due to an attack from phorid flies, individuals with individual flexibility could fill in until more forager caste workers develop. (As a quick aside, another interesting division of labor is discussed in this article that deals more with foraging than caste determination. Apparently, phorid flies tend to attack individuals from the larger castes, so sometimes members of the smaller castes will ride on the leaves of foragers to protect them from the phorid flies. It didn’t really explain whether this was a self sacrifice situation or more of a distraction from the fact that there’s a larger ant under the leaf, but either way it is still pretty cool!). Without this flexibility, the colony would be left crippled by the lack of foragers to collect leaves to feed their fungus gardens. The same would be true of the loss of any other caste. Additionally, the ability to replace them with new specialized adult ants relies on the fact that the developmental pathways stay relatively similar with the ability to change direction (reprogram) easily if need be. Without the flexibility to temporarily replace specialized workers with other workers or to increase the rate at which new specialized workers mature, the colony would lose its ability to perform that function if there were ever a sudden loss in many of a specific caste. For this reason, it is important that a colony strikes a balance between optimizing efficiency through the specialization of castes while maintaining the flexibility to adapt to times of crisis.