Everything’s bigger in Texas… I wish I had a nickel for every time I heard that in the four years that I’ve lived here. This isn’t just a case of Texas pride (which, of course is… bigger) – almost everything in Texas actually is bigger. Take BBQ for example. Or guns. High school football is almost unreal. And cockroaches. The most obscenely large cockroaches I’ve ever seen.

As winter approaches, it has become increasingly difficult to leave the cozy confines of my bed in the morning. Each morning becomes just a little bit cooler than the last. On one particular morning last week, I awoke at 7:15 am for class that would start in about 45 minutes. Of course, by waking up at 7:15 am, I really mean playing the “How many times can I hit my snooze button” game with myself until about 5 minutes before class starts. So there I was, shivering head to toe, throwing on sweat pants, a shirt, and a hoodie as fast as I could so that I could make it to class on time. Everything was going according to plan until I slipped my feet into my shoes, and felt a little prick on my big toe. Whatever, I thought, and continued towards the bathroom to catch a glimpse of myself in the mirror. As I was entering the bathroom, I felt something else in my shoe. As if something was moving a little bit. Strange, I thought, and took the shoe off my foot and shook it upside down. Nothing. I heard a shriek from my roommate, and I looked up to see him pointing towards the outside of my shoe. And there it was. The mystery mover in the shoe, the great tickler of the toes, the Texas-sized American cockroach.

Being the insect nerds that my roommate and I are, we both looked at each other and sang in harmony “BLATTODEA!” (the order of insects to which cockroaches belong). I picked up my shoe and smashed the cockroach to death, and the cockroach was no longer.

But, throughout the day, I couldn’t shake the feeling that my deceased cockroach friend laid eggs inside my shoe and its babies were all waiting for the right moment to strike. Or that maybe there was a whole colony of cockroaches underneath my bed and this courageous individual just happened to wander off into my shoe. Or maybe I brought home all sorts of insects from a recent hike through the woods and were now breeding all sorts of hybrid nasty pests… Why did this have to happen to me?!? Why does Houston have to be filled with so many cockroaches? What was the cockroach doing in my shoe? I searched the Internet for answers.

Houston’s semi-tropical climate is a perfect breeding ground for insects. The high humidity and temperatures combine to create a perfect habitat for cockroaches. However, as daytime temperatures fall in the winter months, cockroaches are found more often indoors, due to their intolerance of cold temperatures. American cockroaches in particular, thrive in warm, humid environments, where they can grow up to 2 inches in length (https://insects.tamu.edu/fieldguide/aimg22.html). Sounds familiar. Especially the up to two inches part.

In addition, cockroaches are mainly nocturnal and run away when exposed to light (http://www.ipm.ucdavis.edu/PMG/PESTNOTES/pn7467.html). So that explains why the cockroach was hanging out inside my shoe as the sun came up in the morning.

Many species of cockroaches, including American cockroaches, only mate one time and are then pregnant for life (http://www.protexpest.com/blog/pest-control/cockroaches-housto/). About every 4 days, females produce a capsule, which contain 13-16 eggs. Then, the females glue their capsules in hidden areas. For instance, inside a shoe. Or underneath a bed. Great.

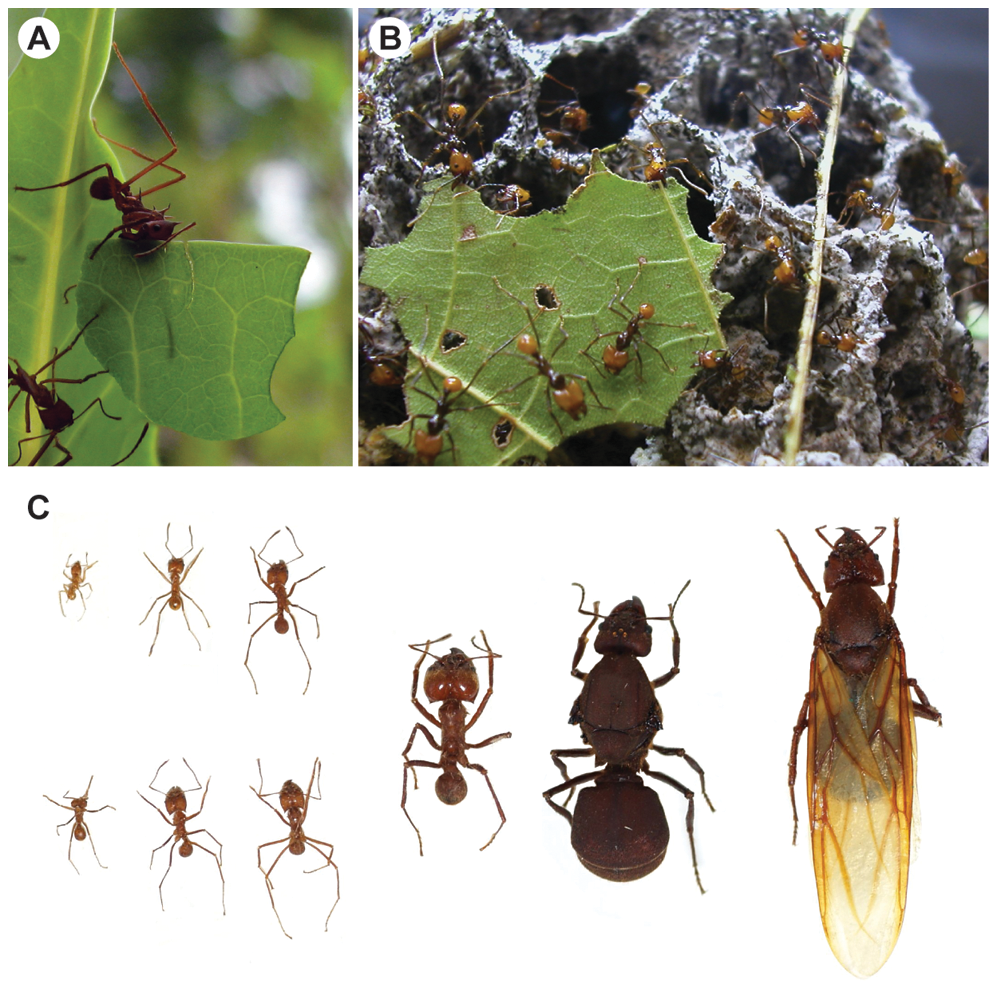

Image courtesy of www.epestsupply.com.

The more I read about cockroach behavioral tendencies, the more worried I became (similar to the webMD paranoia I experience from time to time). As a result, I rushed to CVS and nearly cleared the shelves of all of the pest repellent and cockroach traps it had in stock.

It’s been about a week since my fateful encounter, and thankfully there haven’t been any other cockroach sightings in my dorm. Knock on wood.